|

Guest post by Madison Cammarata ('26). As the Spring 2024 semester drew to a close, my anticipation soared for the upcoming adventure awaiting me: joining fellow students and Professor Harnik in his Paleo Lab. Stepping into this new experience was exhilarating, unlike anything I had ever encountered. Despite the warnings from Professor Harnik about grueling 12-hour days under the sun, unpredictable boat rides, and the looming threat of seasickness, I approached it all with unwavering determination. Fieldwork has always been my favorite part of studying Geology. Exploring stunning outcrops and uncovering fossils has consistently fueled my excitement. Naturally, the prospect of having the new experience of fieldwork on a boat added an extra layer of thrill to the experience. However, our journey hit a rocky start—literally. Despite being prepared for choppy waters and turbulent conditions, my downfall came unexpectedly when my seasickness medication made me feel… seasick. Pro tip: always check for potential interactions before taking meds, or risk ending up like me—dizzy and out of commission. Once I resolved this issue, I could fully immerse myself in the work, appreciating the opportunity to observe fascinating oceanic creatures up close. Alabama was a promising site for our research, particularly in terms of biodiversity and live specimen counts. Discovering the sheer diversity and number of live organisms in each sample astounded me. Among the discoveries, the Nucula proxima, with its stunning shell, stood out as a personal favorite. Before this expedition, bryozoans seemed a bit boring compared to the intricate beauty of bivalve shells. However, after hours spent studying these tiny creatures under the SEM (Scanning Electron Microscope), their mesmerizing complexities were unveiled. My initial indifference transformed into a newfound fascination with these intricate organisms and their exquisite patterns. While my academic focus has primarily revolved around rocks and minerals as an environmental geology major, this research experience provided a compelling introduction to paleontology. Professor Harnik’s research’s emphasis on climate change and the hands-on nature of fieldwork left a profound impact on me. I am immensely grateful for the opportunity, as it has reshaped my perspective on the delicate ecosystems thriving at the ocean's depths.

Guest post by Lindsay Kosnick ('27).

As our group embarked on the long journey to the Gulf, my excitement began to grow. I couldn’t wait to begin my first research experience by getting hands on in the field. I knew there were so many interesting critters and bivalves that could be scooped up and dropped onto my waiting tray. But when we finally got on the boat and things started rocking, everything went downhill. My only experience with boats was on quiet ponds and lakes, so I had no idea that I would get incredibly seasick. No matter what I did or what medication I took, I couldn’t seem to get over it. I spent my days in the field fighting my nausea inside the boat’s cabin and running to the deck to throw up. I couldn’t sit up without feeling sick, let alone work through the samples we were collecting. Needless to say, it wasn’t the trip that I was expecting. Despite my experience being an unpleasant surprise, I still think it was incredibly valuable that I went on the trip. As a rising sophomore, my future is uncertain. I don’t know exactly what I want to do or where I plan to go. There are so many paths to take within Geology, it’s hard to know which one to follow. Throwing up over the side of the boat may not sound like an experience that would provide me any clarity, but it was. Now I know that marine field work may not be for me. I also know that I want to try other field work, just with my feet firmly on the ground. Most importantly, my time on the boat has made me even more excited to get started in the lab. Because of the severity of my seasickness, I was really limited on how involved I could be in the field. Now that we are back in the lab, I can’t wait to finally get to work. Over the next few weeks I’ll be taking a close look at various species and their larval shells. When I find a species that is abundant both live and dead with well preserved larval shells, I’ll be able to work on studying its life history. I’m looking forward to seeing where the lab work takes me. Guest post by Rob Vanderhoef ('27). First, I had never traveled to the Deep South. The fieldwork allowed me to see rural and wetland parts of Louisiana and the chance to see one of our nation's historical cities, New Orleans. Louisiana was much hotter than I anticipated. However, I drank lots of water and applied lots of sunscreen. I also made sure to consume lots of motion sickness medicine before going out each day, and thankfully, I did not throw up the entire trip! Dauphin Island, Alabama, was similar to Louisiana, with both locations showing me more about the Deep South than I previously knew. However, our Dauphin Island experience was more uncertain than Louisiana's. On our second day, the waves were supposed to be around 1-2 feet, but they turned out to be upwards of 6 feet. Fortunately, we could still collect numerous samples at our Alabama sites. Finally, before leaving for our Florida site, Paul and Rebecca informed us that the boat in Florida would not be functional for our offshore travels. Instead, we spent our day off going to the local beach and aquarium and participating in a beautiful riverboat cruise at Wakulla Springs State Park. In the end, I had a fun and eventful time during my fieldwork experience because of our collaborative efforts on the boat and fun adventures when we had days off!! In addition to showing me more about the Deep South and connecting with Paul, Rebecca, and my peers, traveling to the Gulf of Mexico to do field research allowed me to understand the significance of fieldwork and its role in data collection. For example, I could examine the process of sieving the sediment and picking through live organisms and shells, which eventually led back to our work in the lab. The box core on the boat in Louisiana and Alabama brings up sediment samples, meaning there is no way to tell what is present before sieving and picking through it. This uncertainty allowed me to learn so much about the different types of bivalves and examine other organisms that we may or may not study. Before joining the lab, I did not realize that there were so many pathways to take when conducting research about the tiny bivalves we were studying. These included analyzing microstructure, examining ecological and phylogenetic differences across sites, studying population genetics, and much more. I am interested to see what projects the Paleo Lab will take me and my peers on in the future.

Ideally, I want to pursue a career in Conservation Biology. As a double major in environmental studies and biology, my most significant interest is studying how humans affect the environment, specifically how humans affect organisms. The experience in the field only excited my interest in working in the field and with live organisms. Our fieldwork experience showed me the often hidden, yet still significant, steps of storing and shipping specimens. The process of labeling bags and cards, as well as counting the live specimens, often goes overlooked. My time in the field was highly beneficial for my career in the sciences. I know so much more about conducting research, examining data, and answering scientific questions now than ever. Guest post by Emma Lewis ('25). Leading up to our trip to the Gulf of Mexico, we talked a lot about preparing for long days, hot sun, tiring work, and seasickness, and I was nervous to be starting the summer off with what sounded like a less-than-relaxing experience. But when we left the dock in Louisiana the first morning, I was immediately excited just to be out at sea. It was a two hour ride out to the site, and I spent it on the boat deck looking out at the seemingly endless waves, feeling the pleasant (and sometimes hat-threatening) breeze in my face, and watching dolphins swimming in the wake of the boat. I was struck by the power of the ocean and found myself thinking about its vastness and contents. I also spent the ride doing what Paul recommends we do while the microscopes are loading; thinking about my future. As a rising senior, my thesis and the graduate school application process are no longer problems for my distant future. I was feeling anxious about my decision to go to graduate school right after Colgate, and unsure that I had enough experience and information to make the big decision of choosing a graduate program and potentially devoting my future to research. But over the course of this field work, I became much more confident about what I want for my future, and I am very grateful for the experience. I realized that I really loved doing fieldwork - watching the samples come up on the deck, getting covered in mud while sieving, and getting stoked with everyone when we found live clam samples or a cool organism that needed identification were joyful and purposeful experiences for me. I especially enjoyed how Paul and Rebecca, with their different backgrounds, had fascinating knowledge about the species we were finding, and they were learning from each other as well. It showed me how much opportunity there is in interdisciplinary science to spend a whole lifetime learning new things from different people, and I think that marine science is a great field to bring together all kinds of scientific disciplines in cool projects like the ones we are working on now. After this experience, I am excited instead of nervous to be researching marine biology graduate school programs, and I can more clearly envision my future as a scientist. I have learned about marine invertebrates, how research works, graduate school expectations and opportunities, and formed lasting connections with my peers and professors.

Guest post by Olivia Miller ('27).

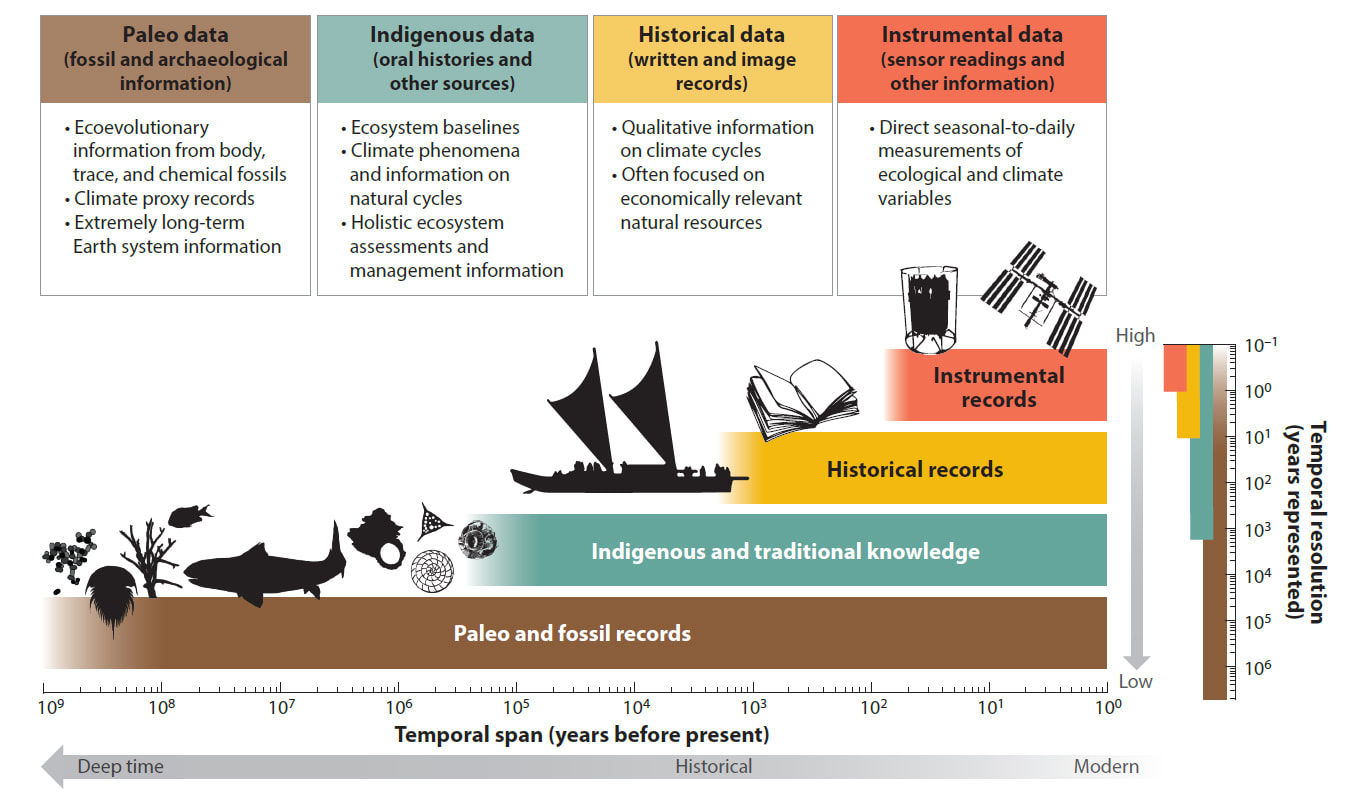

Being on the water was spectacular. Even though we were working hard, it felt like play. I loved making a muddy mess as we sifted through the sediment, and I couldn’t stop laughing as we surfed on seven-foot waves on the rough days. I cherish my memories of cat naps on the sunny bow of the boat, watching dolphins glide through the water at our sides, and getting splashed by rogue waves that lapped up at the open deck while we worked. Even when I felt horribly seasick (enough to warrant me racing to the side of the boat), I was so happy to be out exploring the Gulf. Our fieldwork was a gold mine for curious minds. I didn’t expect to like the work as much as I did, but I found it exciting and fun. Sieving the sediment was strenuous, and picking through the shells was tedious, but there were discoveries to be made with every sample. In our free time, we visited aquariums, went on boat tours, and explored the beach. I thought that at some point, I must get sick of the ocean, but I never did. If anything, I only grew to love it more. I confess that I found that fieldwork in Alabama to be more enjoyable than our time in Louisiana, but that’s probably just because I’d gotten used to some of the more “inspiring” aspects of working on the boat. Our last day on the water was my favorite. Because of rough conditions, we quickly learned that we couldn’t sample at our intended site, so we boated closer to the coast and pulled samples from 10 meters depth rather than our usual 20. I made friends with lots of adventurous snails and crabs that day—we even found a hermit crab hiding in one of the samples! That night, we were told that the boat in Florida needed a repair and wouldn’t be ready for our scheduled visit the next week. I was horribly sad to learn that we wouldn’t be able to sample in Florida after having such a great time in Alabama, but I am incredibly grateful for the opportunities that I was afforded in the week before. If anything, the news made me realize how fortunate we were to be able to get on the water at all, and those memories are even more valuable in hindsight. Our fieldwork was also a great opportunity to get to know the students and professors that I’ll be working with for the rest of the summer—I am lucky to do research with such hard-working, curious, and sincere people. Their jokes and stories made the trip so much more enriching. I was also incredibly impressed by Paul and Rebecca’s unwavering dedication and enthusiasm. Even when we hit some bumps in the road, they kept our morale high. The days on the boat were full and exhausting, and I wouldn’t change a thing (except maybe the absurd number of polychaete worms we had to throw over the deck). I had the opportunity to engage with the samples every step of the way as they traveled from the ocean floor all the way to the microscope in our lab at Colgate. My immersion in this research brought me a newfound appreciation for each tiny little shell that we found. It also makes me excited to learn more about the samples in the lab as I’m reminded of the work we did to retrieve them and the memories we made along the way. How are fossil records used to understand current extinction risk and inform conservation decisions at local to global scales? In our review (available early online here), Seth Finnegan, Rowan Lockwood, Heike Lotze, Loren McClenachan, Sara Kahanamoku, and I provide an overview of the ecological and environmental information available in the fossil record and the application of recent and deep time fossil records in species risk assessment and conservation.

Finnegan, S., P.G. Harnik, R. Lockwood, H.K. Lotze, L. McClenachan, and S.S. Kahanamoku. In press. Using the fossil record to understand extinction risk and inform marine conservation in a changing world. Annual Review of Marine Science 16. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-marine-021723-095235 How do environmental conditions influence predator and prey body size? Luke Calderaro ('22), Marina Rillo, and I addressed this question by studying the empty shells of marine bivalves, and the predatory traces (drillholes) left behind by drilling gastropods, at sites located on the continental shelf between Louisiana and Florida. Luke measured more than 3000 bivalve shells and associated traces of drilling predation, and we worked with Marina to compile environmental data for our 15 stations. Using mixed-effects models, we examined the associations between environmental conditions and predator and prey size, while accounting for the sizes of different bivalve genera. Overall, we found that bivalves tend to be larger in low oxygen settings where predation is greatly reduced, and that the sizes of predators and prey tend to increase with sea surface temperature. To learn more, you can read our open-access article in Paleobiology here: link.

Calderaro, L.A., P.G. Harnik, and M.C. Rillo. 2023. Environmental correlates of molluscan predator-prey body size in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Paleobiology. Post by Alexa Russo (Colgate '25)

My time in the Gulf was extremely valuable; from getting to see all the specimens - both ones we study and ones we don’t - up close and personal, to getting to have conversations with crew members, other students, interns, and scientists. While we primarily study marine bivalves (clams) in the Paleo Lab, we can’t control what gets picked up by the box core on the seafloor when we are sampling, which leads to us seeing so many cool critters like crabs, worms, sea stars, and even eels. I was able to learn so much over the course of three weeks, and I really enjoyed hearing about everyone’s interests and specialties, and learning about all the different career paths there are, and all the different fields of study that exist within the marine sciences. I especially enjoyed talking with two scientific scuba divers who helped us collect samples; I had never really thought about how useful scuba diving can be for scientific studies, and we talked about the process of getting certified to dive for scientific purposes. While I personally don’t see myself being a marine scientist in the future as I am more interested in terrestrial paleontology for my future career, the skills I learned from being in the field will be extremely useful in the future regardless of the path I choose to take. I learned new field techniques, ways to collaborate with other scientists, and how scientists may come up with new projects or questions they want to answer. Additionally, I learned a lot about the importance of organization and labeling, even when you’re covered in mud on the back of a boat. After all, if we don’t know exactly where a sample came from, the data we get from it won’t tell us much, especially when we are studying the impact of environmental conditions on marine life. Overall, my experiences in the field will stick with me and be a benefit to my future, and I hope to apply the field skills I learned in the near future. Post by Riley Farbstein (Colgate '24) Before embarking on our trip to the Gulf of Mexico, I found myself a bit nervous. I worried about being on a boat for up to 12 hours a day with a group that I barely knew. Little did I know this experience would be one of the best choices I have made during my undergraduate career. I loved being on the boat all day; the work was engaging and fascinating. Although getting up at 5:45 AM to depart the dock at 7:00 AM was definitely a struggle for me, I was eager to get out of bed and explore what each day had to offer. The early mornings also became easier as the trip went on. I looked forward to the early morning boat rides to our sites in Louisiana. Every morning, my lab partners and I sat at the front of the boat and enjoyed the company of dolphins. The dolphins always seemed to strangely appreciate our presence in the channel and, almost every day, were found riding the vessel's wake. Each site that we visited offered different and exciting finds. Whether it was the number of live clams we observed, other sea life, or the diversity of shelled species, each site had a unique experience to offer. My favorite job on the boat involved sorting through shells that were collected using a box core. With the help of the crew from each marine lab, sediments and other materials on the seafloor (around 20 m deep) became accessible to us. I found multiple shark teeth in Louisiana, which was my favorite find. With each tiny live clam found, joy and excitement fueled my body, encouraging me to continue sorting through the biomineralized material. In Alabama, one of my favorite moments working offshore was the once-in-a-lifetime experience of dipping into the Gulf of Mexico. On this day, I was exhausted due to the extreme heat and humidity. After joking with Grant, one of the crew members, about taking a swim off the boat, Grant shockingly replied, “Well, why don’t you jump in!” In the corner of my eyes, I saw Paul look over in horror, shaking his head. After negotiating with Paul, and further discussing logistics with Grant, we were allowed to jump into the Gulf IF we wore life preservers and held on to a rope attached to the boat. To relieve ourselves from the heat, Marie, Mary Thomas, Ryan, and I jumped off the ship and enjoyed the refreshing waters of the Gulf. Although a bit unnerving, being unable to see land and feeling people accidentally rub against me in the sea, it was a moment I will never forget. After the “studes” jumped into the Gulf, our goal was to get Paul in the water. He agreed after various negotiations and agreements regarding how much work we needed to accomplish. Despite this, Paul never jumped in due to changing weather conditions and safety concerns regarding the waves. I am genuinely thankful for my experience and found the work engaging and scientifically significant. As a rising senior, the samples we collected offshore will be used for my senior thesis research. As a hands-on learner, I found it beneficial to physically process and understand the methods involved in collecting these specimens. Through my engagement with the sampling process, I better understand the material that I will be analyzing and working with next school year. Additionally, this experience opened up my interest in possible career paths in the future. Although I am still determining what I would like to do in the future, this trip has taught me that I could see myself working or studying marine biology, paleontology, and/or conservation. I would love to thank my fantastic advisor, Professor Paul Harnik, for suggesting the research experience. His optimism, bad taste in music, dad jokes, and humor motivated the group and encouraged a positive work environment. I also thank my fellow classmates and researchers for the endless laughs and fun brought about by working and living together. Finally, this research trip would not be possible without the help and work of the crew members at LUMCON (Louisiana) and the Dauphin Island Sea Lab (Alabama).

|

Proudly powered by Weebly